Tutorial - Getting Started with Roboconf

Introduction

This tutorial aims at introducing the basis to work with Roboconf.

It will help you to…

- … install Roboconf’s administration, the DM (Deployment Manager).

- … learn the basis to administer Roboconf.

- … simulate the deployment of a distributed application.

This tutorial was written for Linux systems.

However, it should also work on Windows and Mac.

Installation

In the scope of this tutorial, you will only use Roboconf’s administration. It is called the DM (which stands for the Deployment Manager). You will also use a messaging server, RabbitMQ.

Download the DM on this page.

You will need a Java Virtual Machine to run it (JDK 7).

To install it, unzip the archive. It may be better to prefer the *.tar.gz archive, since this format preserves

file permissions.

About RabbitMQ, please refer to our user guide which explains the procedure to install it.

Administration

Now that installation is over, let’s explore the configuration and the available commands in the DM. First, you need to tell the DM where the messaging server (RabbitMQ) runs.

The DM is a set of Java libraries, and more exactly, as OSGi bundles.

The DM is packaged a Karaf distribution. It means you have downloaded

an OSGi server with everything installed and (almost) ready to be used.

Open the etc/net.roboconf.dm.configuration.cfg Karaf file.

Update the messaging properties (URL, user name, password). You defined these properties when you installed the messaging server.

Update also the location of the directory that will be used to store applications and their states. By default, everything is stored

in the system’s temporary directory.

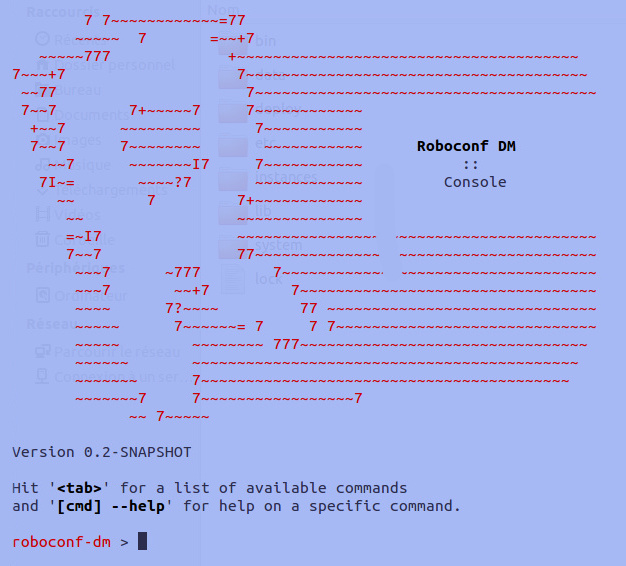

Then, execute the bin/karaf file.

A new shell should appear. You will use it to enable or disable Roboconf extensions.

Type in the following command.

bundle:list

This command lists all the deployed bundles.

Notice that some are marked as started, while others are only installed. This is the case of extensions

that are related to deployment infrastructures (Amazon Web Services, Openstack, Docker…). Nobody use all these

infrastructures at the same time. So, it is better and more optimal to only enable those that are required.

Type in this new command.

feature:list

This command lists features, that is to say, groups of bundles.

Most of them are not installed. Those that are installed have their bundles listed by the bundle:list command.

Beyond this command line interface, Karaf provides various features that the DM uses. You will find logs under the data/log directory. And the configuration of the various services is located under the etc directory. Their properties can be updated at runtime. It means the changes are applied without rebooting the platform.

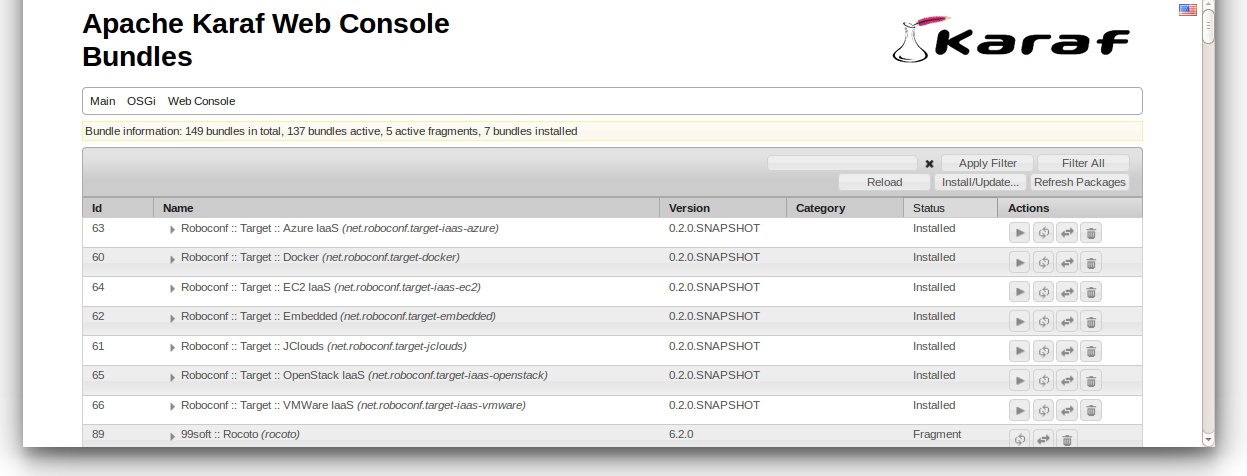

Web Console

Karaf comes with a web console.

By default, it is available at the following address: http://localhost:8181/system/console.

Default credentials are karaf / karaf.

You should not have to use it in this tutorial. But is is always useful to know it exists and that it is here.

Preparing the Simulation Mode

Before deploying your first Roboconf application, you need to prepare the platform to use the simulation mode. This requires some additional bundles to be installed.

Hopefully, Karaf allows to deploy bundles directly from Maven repositories.

In Karaf’s command line interface, execute the following commands. We here assume you use Roboconf 0.4.

bundle:install mvn:net.roboconf/roboconf-plugin-api/0.4

bundle:install mvn:net.roboconf/roboconf-agent/0.4

bundle:install mvn:net.roboconf/roboconf-target-in-memory/0.4

Every time you install a bundle, it gets an identifier.

Use these identifiers to start these bundles (replace id1, id2 and id3 by their values).

bundle:start id1 id2 id3

List the bundles and verify they are started (and not just installed).

Check also Roboconf’s logs. You should find the following mention…

Target handler 'in-memory' is now available in Roboconf's DM.

When you started the in-memory extension, it was automatically detected by the DM. The exact term is that it was injected into the DM’s main class. If you stop the bundle, the extension will be unregistered. Several Roboconf features can be enabled or disabled in this way.

First Roboconf Application

You are now going to deploy your first Roboconf application.

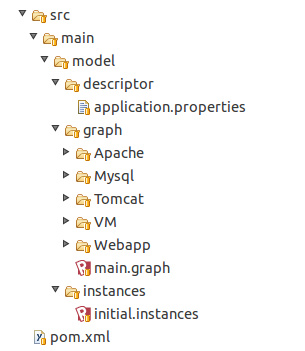

Download it here. It is a ZIP archive with a specific structure

(it always contains the following directories: descriptor, graph and instances).

The descriptor part is quite simple to understand. But the graph one needs some explanations. Open the main.graph file. It defines Software blocks. And it contains the various relations that link these blocks together. Roboconf knows 3 kinds of relations.

-

Containment: a Software block must be deployed on or within another one.

Ex: an application server must be deployed on a machine, an application must be deployed in a server… -

Runtime: a Software block uses and depends on another one.

Ex: an application relies on a database, it cannot work without it. -

Inheritance: a Software block is similar to another one, or adds new properties.

Ex: a database for clients and another one for products. In both cases, we can have the same solution. Same version, same installation, same start process, etc. But they have different roles and a different name to distinguish them. Inheritance is a way of reusing things in a graph.

Observe the file that the defines the graph.

There is no inheritance in this example. Containment relations are defined through the children keyword.

Runtime relations are defined through the imports and exports keywords. They define variables that will be exchanged

between Software blocks at runtime. This is where the messaging server is used.

Then, notice that for every Software block (Roboconf component), there is an eponym directory.

Every directory contains recipes (or resources) to deploy the component. Recipes handle the entire life cycle of the component

(deploy, start, stop, undeploy). They also react to dependency changes. Thus, Roboconf guarantees that if a dependency disappears,

the component will be stopped. It will be restarted as soon as all the dependencies are resolved.

Dependency resolution is useful for massive concurrent deployment.

Dependencies are resolved asynchronously by Roboconf. This mechanism is also used to manage elastic deployments on platforms that rely on Roboconf.

The way recipes are written depends on a component property called installer. As an example, if a component uses the bash installer, then Bash scripts are used to handle the component’s life cycle. If it is the puppet installer, then a Puppet module is used. And so on…

Eventually, take a look at the instances root directory (in the archive).

The graph is in fact a set of rules, just like a meta-model. You have to define instances then. A (component) instance

is a Software block that is or will be deployed somewhere. When you use Roboconf’s web administration, you manipulate instances.

First Deployment

You must have noticed in the graph there is a component called VM. It is associated with the target installer. Basically, this is you target machine. If you study the content of the graph/VM/target.properties file, you will see it is configured to be an in-memory target.

When you deploy a VM instance, Roboconf reads the content of this file and determines what it has to do. The target-id property references a Roboconf’s extension (here, the one you installed previously, the target-in-memory). This extension uses this file to create your VM on the target infrastructure you chose. Therefore, if you want to switch from an in-memory VM to a VM on Amazon Web Services (or any other supported cloud), you only have to update the target.properties file.

Here, the deployment of a VM will create a new Roboconf agent in memory. Every target machine must have a Roboconf agent. This agent is in charge of managing the deployments and the other actions on its machine.

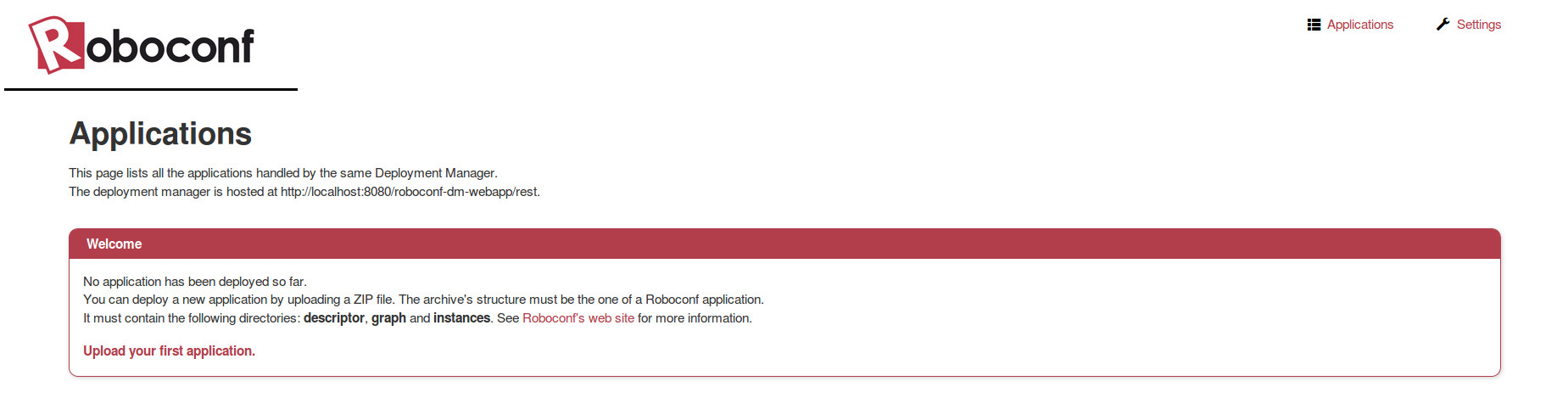

Open your web browser and go to http://localhost:8181/roboconf-web-administration/index.html.

Check that the configuration is valid. Then, upload the application’s archive. Once it is upload, play with the life cycle of the components. To manipulate a component, it is important for its parent (or container) to be deployed and started. The only exception is about root instances. Root instances designate machines. They only know 2 states: deployed and started, and not deployed. The reason for this is that some virtualization infrastructures do not support an intermediate state like deployed but stopped.

To test dependency resolution, try to the following scenario.

Make sure everything is not deployed first.

-

Deploy and start the load balancer.

The Apache server should remain in the starting state. This is because its dependencies (the web application) is not yet started. -

Proceed in the same way with the web application.

It should also remain in the starting state. This is because the database is not yet started.

3.Eventually, deploy and start the database.

All the components should now be started.

Every time a component is started or is stopped, it publishes notifications on the messaging server (RabbitMQ). Components that depend on it are thus notified of its state and of its variables (IP address, port, etc). The components (or Software blocks) do not deal with these notifications themselves. They are handled by Roboconf agents. There is one agent per machine. Here, agents run in memory (simulation mode). With real deployments, the agent must be installed on the remote machine and run (ideally, it should boot with the system). All of this can be made automatic, in particular with virtualization platform. This includes cloud computing infrastructures.

A last element to detail is what happens when you trigger an action from Roboconf’s web administration. Since we are here in a simulation mode, Roboconf only changes components states. On a real infrastructure, agents would also execute the recipes that come along with the graph. Notice also that a user action is not always followed by a concrete action. When a user clicks somewhere in the web administration, it only sends a request to the right agent. Validating, executing or even dropping this request is the responsibility of the agent.

Conclusion

You have completed the first Roboconf tutorial.

And you should now be familiar with the DM, RabbitMQ and their installation.

You played with the command line interface and roboconf’s web administration. Eventually, you also studied and

deployed a first application with Roboconf. As you could see, there is no constraint on what can be deployed with Roboconf

(no constraint on the architecture, no constraint on programming languages).